The T-Shirt as a Living Artifact: From Anonymity to Cultural Icon

Introduction

Once a simple utility garment hidden beneath layers of formalwear, the T-shirt has become an omnipresent and expressive element of the global wardrobe. Worn by every demographic across geography, class, and profession, it is a garment that transcends fashion and functions as a medium for storytelling, activism, identity, and innovation. Its ubiquity often obscures its complexity; however, the T-shirt is not just a mass-produced object of convenience. It is a living artifact—evolving with society, bearing the marks of every era, and adapting to our shifting social, political, environmental, and technological landscapes. This essay traces the comprehensive narrative of the T-shirt, moving from its hidden beginnings to its present status as a global cultural canvas and projecting forward to its dynamic future in a circular, digitally augmented world.

Historical Foundations and the Rise of Informal Dress

The T-shirt did not arrive fully formed in the modern world. Its origin can be traced back to late-nineteenth-century Europe and the United States, where it evolved from one-piece undergarments known as union suits. As industrial work environments and military operations demanded more agile, breathable options, the union suit was split into top and bottom components, giving birth to the crewneck undershirt. These early shirts were designed not to be seen but to serve as a hygienic and absorbent layer between skin and formalwear.

During the first half of the twentieth century, the T-shirt’s evolution accelerated under the conditions of war. In both World Wars, American and European soldiers wore lightweight cotton T-shirts beneath their uniforms. These garments provided comfort in hostile climates and were easier to clean than their heavier outerwear. Soldiers began to wear them casually during downtime, particularly in tropical outposts, where temperatures made heavy fatigues impractical. Upon returning home, veterans continued to wear their T-shirts, introducing them to civilian life in a context of leisure and informality.

This cultural migration of the T-shirt from the battlefield to the backyard coincided with broader postwar shifts in dress codes and values. Hollywood icons like Marlon Brando and James Dean redefined masculinity through the lens of rebellion and rugged simplicity. Their on-screen appearances in plain white T-shirts resonated with a generation eager to shed the constraints of prewar formality. From these moments, the T-shirt gained a new visibility and symbolic charge, transforming it from an undergarment into a statement piece.

Technological Progress and Fiber Innovation

The T-shirt’s journey is inseparable from the development of textile technology. Early cotton T-shirts were made from carded yarns with low twist, which made them comfortable but prone to deformation and wear. As demand for durability and consistency grew, textile producers began to refine their methods. Ring-spun cotton, introduced during the mid-twentieth century, involved twisting and thinning the cotton fibers more tightly to create a smoother and stronger yarn. This advancement led to a longer-lasting shirt that retained its shape and withstood repeated laundering.

As synthetic fibers rose to prominence, the T-shirt underwent another metamorphosis. Blends of cotton with polyester, rayon, and eventually elastane gave rise to performance garments that resisted wrinkles, dried faster, and stretched with the body. These materials also enabled new printing techniques and finishes, which opened creative avenues for designers and brands.

Today, the most significant developments in T-shirt production come from the intersection of sustainability and biotechnology. Organic cotton, which eschews synthetic pesticides and herbicides, has become a staple among eco-conscious brands. Regenerative agriculture seeks to go even further by using cotton cultivation as a means of restoring soil health and increasing biodiversity. Meanwhile, bioengineered fibers—created from algae, mushroom mycelium, or recycled food waste—promise to replace petroleum-based synthetics and minimize resource consumption.

Equally transformative are manufacturing techniques that reduce waste and water use. Whole-garment knitting technologies can produce seamless shirts directly from digital patterns, eliminating fabric scraps. Dyeing methods that use carbon dioxide instead of water drastically cut environmental impacts. As these technologies scale, they may fundamentally reshape how T-shirts are designed, produced, and valued in the global economy.

Symbolism, Protest, and Pop Culture Relevance

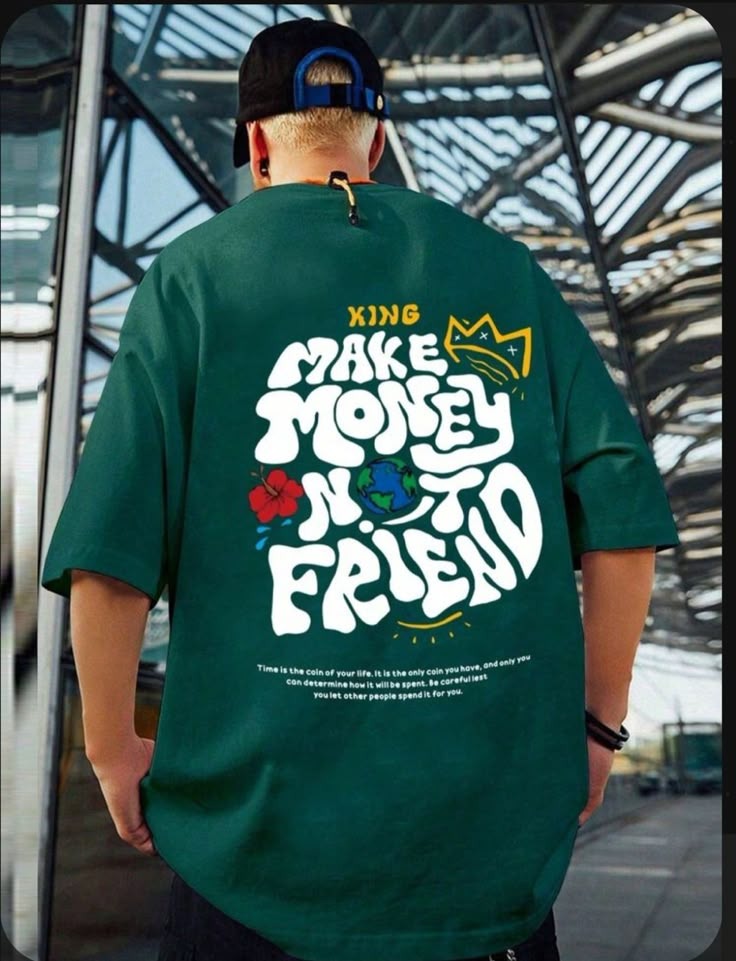

Perhaps no other piece of clothing has served so frequently as a billboard for personal and political expression as the T-shirt. Its flat surface, wide visibility, and low production cost make it an ideal platform for messaging. From punk rock slogans to political campaigns, corporate logos to social justice movements, the T-shirt has become a walking declaration of belief and identity.

During the countercultural movements of the 1960s and 70s, screen-printed T-shirts emerged as a democratized medium of protest. Antiwar activists, environmentalists, feminists, and civil rights leaders all adopted the T-shirt as a means of reaching the masses. Simple graphics like the peace sign or the raised fist took on monumental significance when replicated across thousands of torsos.

In the decades that followed, brands and artists began to recognize the power of T-shirts to communicate not only ideas but status. Fashion houses such as Chanel and Dior began producing branded T-shirts that blended haute couture with streetwear aesthetics. Simultaneously, independent designers and underground labels used limited-run T-shirts to cultivate subcultural credibility. The rise of hip-hop and skateboarding further entrenched the T-shirt as a symbol of defiance, creativity, and authenticity.

In the current era, the T-shirt continues to serve as a barometer of cultural mood. From Black Lives Matter slogans to climate action graphics, from viral meme shirts to metaverse-native designs, the T-shirt has retained its unique role as both reflector and catalyst of contemporary life. It is not merely a canvas; it is an instrument of participation in the social, political, and aesthetic dialogues of our time.

The Economics of Fast Fashion and the Ethical Challenge

Beneath the cultural prominence of the T-shirt lies a complex and often troubling economic system. Mass-market retailers produce billions of T-shirts each year, often priced below the cost of a sandwich. This affordability is made possible by globalized supply chains that rely on low-wage labor, resource-intensive farming, and energy-inefficient logistics.

The social cost of this system is immense. Many T-shirts are sewn in factories with inadequate labor protections, where workers—many of them women—face unsafe conditions, long hours, and wages far below living standards. Despite rising consumer awareness, progress remains slow, and transparency is often obscured by subcontracting and offshoring.

The environmental cost is equally dire. Conventional cotton farming depletes water reserves and contributes to soil degradation. The dyeing and finishing stages of T-shirt production account for large portions of the industry’s chemical pollution. Discarded T-shirts often end up in landfills or are shipped to developing countries, where they may overwhelm local economies and infrastructure.

In response, a growing movement of ethical fashion brands is challenging the status quo. These companies prioritize fair trade certification, circular supply models, and full lifecycle transparency. Some offer take-back programs or repair services to extend garment longevity. Others are experimenting with digital ID tags that store material origin, labor history, and recycling instructions, creating accountability through blockchain-backed supply chains.

Design, Fit, and the Personalization Frontier

While the T-shirt’s anatomy remains relatively unchanged—a torso panel, two sleeves, and a neckline—its design has become an art form. Designers play with proportion, texture, and silhouette to reinterpret the form for diverse bodies and identities. Oversized cuts evoke streetwear and hip-hop culture, while slim fits cater to athletic or minimalist aesthetics. Cropped styles, asymmetrical hems, exaggerated sleeves, and sculptural draping all signal fashion’s continual reinvention of the ordinary.

Personalization has reached new heights in recent years. Print-on-demand technology allows consumers to design their own graphics, upload photographs, or select fonts for one-off creations. Embroidery services let people add monograms, symbols, or illustrations. Advanced scanning software enables custom-fit T-shirts based on individual body measurements, enhancing comfort and reducing returns.

Beyond aesthetics, personalization now includes interactivity. Augmented reality features, activated via smartphone apps, allow wearers to animate their T-shirts with virtual art or hidden messages. Near-field communication chips embedded in shirt labels can link to digital portfolios, social profiles, or protest petitions. These developments suggest that the T-shirt of the future will be as much a medium of communication as of clothing.

Repair, Upcycling, and the Slow Fashion Revival

The final frontier in the T-shirt’s evolution may be its embrace of impermanence and reinvention. The fast fashion model has conditioned consumers to dispose of garments at the first sign of wear. Yet a counter-trend is emerging that sees repair as a form of care and storytelling. Visible mending techniques like sashiko and darning are gaining traction among consumers who see value in preserving and personalizing their clothing.

Upcycling, too, is transforming how we think about the end of a garment’s life. Old T-shirts can be reimagined as patchwork quilts, reusable bags, wall art, or accessories. Fashion collectives and DIY creators use surplus shirts to create entirely new silhouettes—skirts from layered tees, jackets from quilted remnants, or jewelry from shredded hems. These practices promote sustainability but also creativity, inviting consumers to become co-creators in the garment’s lifecycle.

Educational programs and online communities further support this ethos by teaching people to sew, dye, and alter their own clothing. In doing so, they not only reduce waste but reconnect wearers with the human skills and stories embedded in every seam.

Conclusion

The T-shirt, in its apparent simplicity, holds multitudes. It is a reflection of industrial history, a site of technological innovation, a vehicle for protest, a badge of affiliation, and a blank slate for personal expression. It speaks to the conditions under which it is made, the values of those who wear it, and the aspirations of societies in transition. As we move into an era defined by ecological constraint and digital expansion, the T-shirt will continue to evolve—reimagined through new materials, ethical frameworks, and augmented experiences. But even as it transforms, it will remain what it has always been: a second skin for the collective human story.